Over one-third of full-time workers say they frequently check email outside normal working hours.

Like many of you, I often work outside regular office hours while at home, in the airport, or on vacation. Mobile technology has created a "new normal" work life for a lot of us: Gallup research reveals that nearly all full-time U.S. workers (96%) have access to a computer, smartphone, or tablet, and 86% use a smartphone or tablet or both. A full two-thirds of Americans report that the amount of work they do outside normal working hours has increased a little to a lot because of mobile technology advances over the last decade.

But is this a net gain or net drain on our well-being? And how should leaders manage this after-hours work?

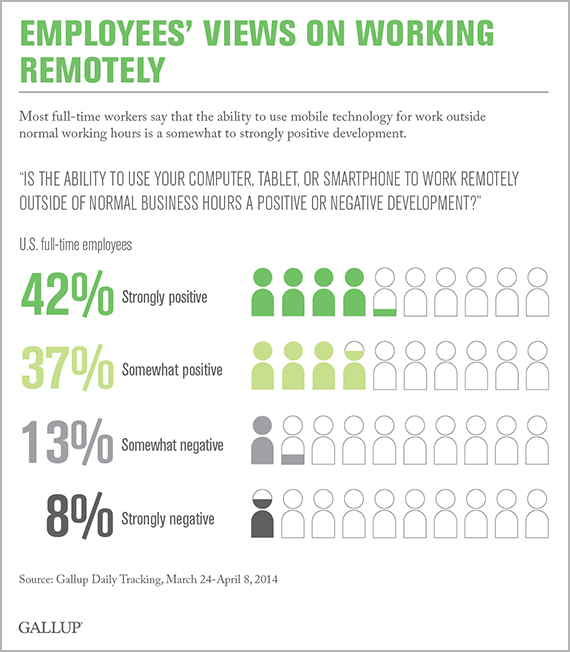

To answer these questions, it's important to understand why we turn to mobile technology in the first place. For many people, it's because we're excited to share an idea with a colleague or want to finish a task so it doesn't become a burden the next day. Yes, taking care of work during non-work time may hurt our relationships with family and friends. But more than three-quarters of full-time workers tell Gallup that the ability to use mobile technology outside normal working hours is a somewhat to very positive development.

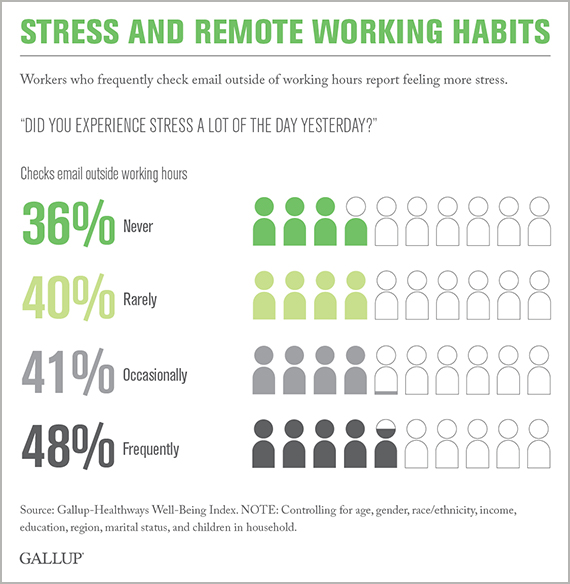

Going deeper, we found that just over one-third of full-time workers say they frequently check email outside normal working hours -- and those who do are 17% more likely to report better overall lives compared with those who say they never check email outside work. This finding holds true even after controlling for differences in income, age, gender, education, and other demographics. Similarly, workers who spend seven or more hours checking their email outside work during a typical week are more likely to rate their overall lives highly than those who report zero hours of this activity.

But here's the conundrum: About half of workers who report checking email frequently outside work are also more likely to report having a lot of stress the day before, compared with just one-third of those who never do.

In other words, the "evaluating self" disagrees with the "experiencing self." The evaluating self probably says life is better because we have the flexibility to check email when we want, while the experiencing self feels the stress associated with the extra work, pressure, or guilt during our after-hours working time.

Checking email frequently is stressful -- but associated with status

This inner conflict between the evaluating self and the experiencing self is not new to psychologists. For example, research suggests that our two selves also differ in how they interpret having money and children. Being a parent and having more money is associated with higher life evaluations. But above a baseline of income, having more money doesn't relate to less daily stress, and having kids brings more daily stress, on average.

In other words, the evaluating self responds to status, while the experiencing self responds to daily and momentary life. Thus, though checking email frequently appears to be stressful, it is also most likely associated with status and perceived importance.

So for optimal workplace well-being, what should employers do to help workers solve this conundrum? Expect workers to check in during non-normal working hours? Or implement policies that discourage work during non-normal work times?

Employees who say their employer expects them to check email outside normal working hours report stress 19% more frequently than those whose employer doesn't expect them to check email. This might lead employers to think they should put the needs of employees' experiencing self ahead of their evaluating self and place specific parameters around expectations that employees check in during off hours.

Not so fast.

Problems arise when companies make such policy decisions without considering whether their employees are engaged. If we believe work can be engaging and rewarding, rather than a necessary burden, our understanding of people and policy is quite different.Die meisten Vollzeitmitarbeiterinnen und -mitarbeiter sehen in der

Most full-time employees consider the option to use mobile technology away from work an advantage.

Daily stress is lower for engaged employees

Gallup has identified three types of workers: engaged, not engaged, and actively disengaged. Thirty percent of U.S. workers are engaged -- they are involved in and enthusiastic about their work and company. At 52%, not engaged workers make up the vast majority of the U.S. workplace -- they are indifferent and basically just show up, do the minimum required, get their paycheck, and go home. Actively disengaged workers comprise 18% of the U.S. workforce and actually work against the aims of the organization. Gallup measures engagement through 12 elements that explain differences between highly productive and less productive workplaces.

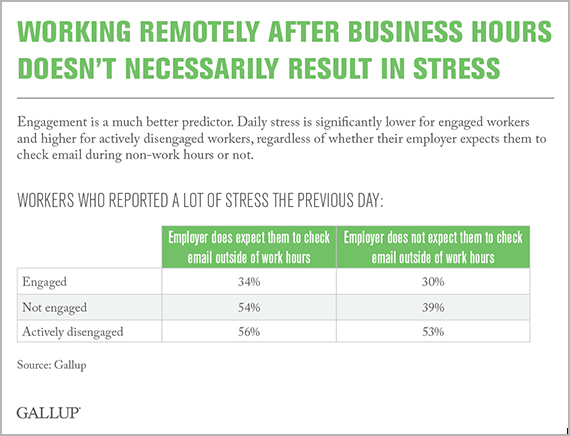

Daily stress is significantly lower for engaged workers and higher for actively disengaged workers, regardless of whether their employer expects them to check email during non-work hours or not. And the vast swath of not engaged or indifferent workers are most influenced by policy decisions of this nature. Among not engaged workers who say their employer expects them to check email outside normal working hours, 54% report a lot of stress the previous day. Of those who say their employer does not expect them to check email, 39% report a lot of stress.

These findings suggest that workers will view their company's policy about mobile technology through the filter of their own engagement. Thus, instead of tinkering with their policies, companies would be better off developing a strategy to engage more of their employees. For instance, though more hours worked, less vacation time taken, and less opportunity for flextime generally relate to lower well-being in our studies, that doesn't hold true when workers are engaged in the workplace. It turns out that among engaged employees, their well-being remains high regardless of these types of policies. As an extreme example, employees with six or more weeks of annual vacation time who are actively disengaged in their work and workplace have lower overall well-being than those who are engaged and have less than one week of vacation time.

Similarly, though long commutes generally relate to lower well-being in the average non-engaged worker, it isn't true for those who are engaged. Our research shows that well-being levels are similar among engaged workers, regardless of their commute time. These findings underscore the importance of employee engagement to workers' well-being in the workplace. Engaged workers are more productive and profitable; are more likely to show up to work regularly and make a difference with customers; and are loyal, advocating partners to the organization. They view their lives more positively because they work in organizations that get the most out of their talents.

The importance of hiring and developing quality managers

Though just 30% of employees in the U.S. and 13% worldwide are engaged, it doesn't have to be that way. Many organizations -- even large international organizations -- have more than doubled these percentages by not accepting a fatalistic status quo. Through quality measurement, accountability, developmental plans, good communication, and aligned strategy, these companies have developed environments where the norm is for workers to be engaged rather than indifferent. This starts and ends with hiring and developing quality managers who have the natural talents and skills to engage and develop each person they manage, thereby improving how people evaluate their lives and experience their days.

Most full-time employees consider the option to use mobile technology away from work an advantage rather than a hindrance, probably because of the flexibility it allows. With the help of great managers, engaged employees take advantage of this flexibility without feeling extra stress. And though organizations can set blanket policies that assume indifference among employees, they might be better off engaging them first. Policies are important -- but they shouldn't be any manager's starting point.

A version of this article originally appeared in the HBR Blog Network.