People Management: Pros, Cons and Development Opportunities

- What Is the Role of a Manager?

- What Is the Importance of a Manager?

- Employee Experience: The Manager Makes the Difference

- What Are the Biggest Challenges of Management?

- What Are the Perks of Being a Manager?

- Is Management a Good Career Choice?

- How Can Leaders Better Support Their Management?

- How Gallup Can Help

01 What Is the Role of a Manager?

Gallup defines a "manager" as someone who is responsible for leading a team toward common objectives.

The role of a manager won't be the same for all organizations. Oftentimes, though, managers have a multitude of responsibilities, from communicating an organization's vision to daily management duties like coordinating work, making decisions and solving problems. Their responsibilities range from getting work done through others to completing their own assignments, to engaging and developing their team members.

The manager is often instrumental in deciding whom to hire, how to position or advance an employee, and whom to let go. They may make decisions about workload distribution and allocation of team resources. And they may work to advance or repair customer relationships.

While the role of manager may differ from business to business, Gallup has discovered that many managers best serve their companies as coaches, not command-and-control style bosses.

- Inspiring teams to get exceptional work done

- Setting goals and arranging resources for the team to excel

- Influencing others to act; pushing through adversity and resistance

- Building committed teams with deep bonds

- Taking an analytical approach to strategy and decision-making

02 What Is the Importance of a Manager?

Managers are the heart of an organization.

Nearly every problem and achievement in an organization can be tied back to the quality of the managers.

Why? Gallup has found that the role of the manager is a dominant factor in the employee experience -- from onboarding and performance to development and retention.

Managers account for an astounding 70% of the variance in team engagement, and their efforts substantially impact the bottom line of entire organizations.

So it should be no surprise that how managers feel about their organization greatly influences how they go about managing people at work. In other words, the manager experience largely defines the employee experience.

Gallup studied over 50,000 managers from 2014 to 2019 and asked them more than 500 questions about how they experienced their workplace. Our experts analyzed survey data, conducted interviews and facilitated focus groups. We did real-time ethnographic studies of "a day in the life of a manager" and we did retrospective "day reconstruction" studies. Our researchers scoured countless performance metrics, talked to "manager of the year" award winners and studied what the best do differently.

What we discovered is that the manager experience is complicated and dynamic, filled with opportunities but also frequent pitfalls.

03 Employee Experience: The Manager Makes the Difference

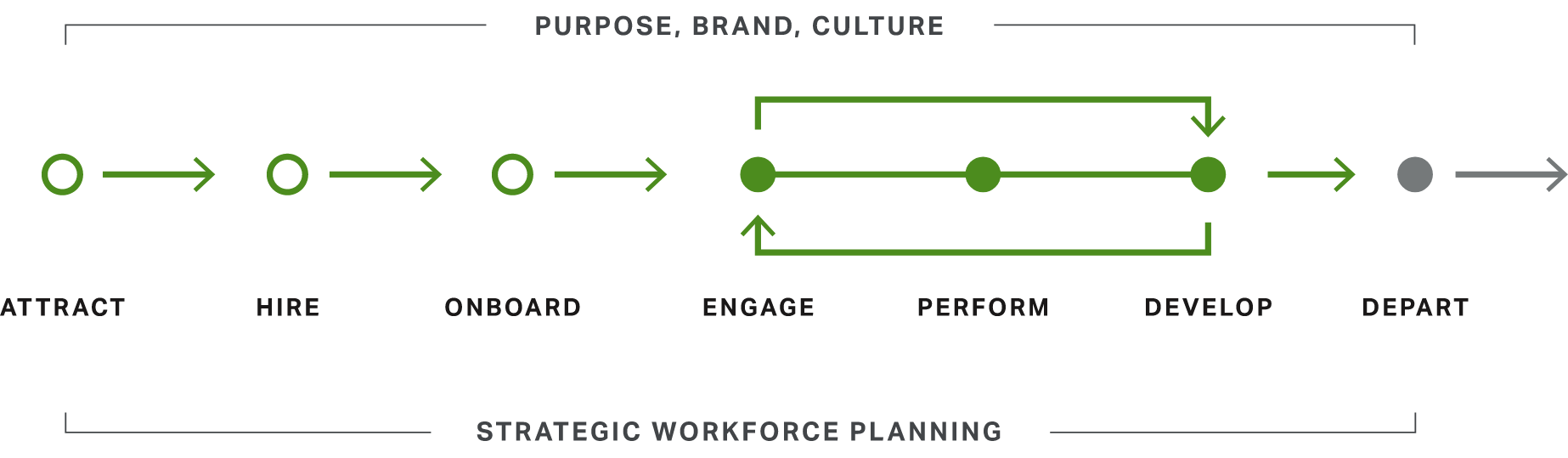

The manager plays a pivotal role in the employee experience. They are involved in every major milestone of the employee journey, from onboarding to exit, and their interactions with employees are typically the dominant factor in positive outcomes at each stage. For this reason, leaders need to look carefully at their employee experience strategy: Are managers set up for success at each major stage of the employee experience?

Attract

Millennials report that "quality of manager" and "opportunities to learn and grow" are among the top factors they value when joining an organization.

Hire

When managers create a positive experience during the hiring process, new employees feel excited they were chosen to work for a manager who appreciates their talents and will be more invested in their career.

Onboard

When managers play an active role in onboarding, employees are 2.5x more likely to strongly agree their onboarding process was exceptional.

Engage

Employees who receive daily, meaningful feedback from their manager are 3.5x more likely to be engaged than those who receive feedback once a year or less.

Perform

Only two in 10 employees strongly agree that their performance is managed in a way that motivates them to do outstanding work.

Develop

When managers develop employees based on their strengths, employees are more than twice as likely to be engaged.

Depart

Fifty-two percent of exiting employees say that their manager or organization could have done something to prevent them from leaving their job. Nevertheless, only 51% of employees who chose to leave had a conversation about their engagement, development or future in the three months prior to leaving.

04 What Are the Biggest Challenges of Management?

The challenges of management are not insignificant.

Managers juggle competing priorities, unclear expectations and heavy workloads.

Their days are often long, filled with meetings, distractions at work and high-stakes decision-making. They must take risks that could lead to better ways of doing things -- or they could fail. Managers also are expected to take on tasks that may not align well with their strengths, which adds to their job stress.

Caught in an endless cycle of urgent work, managers are often unhappy with the very systems built to help them. Performance reviews and career development programs tend to be particularly disappointing to managers.

The top five challenges of management:

1. Unclear Expectations

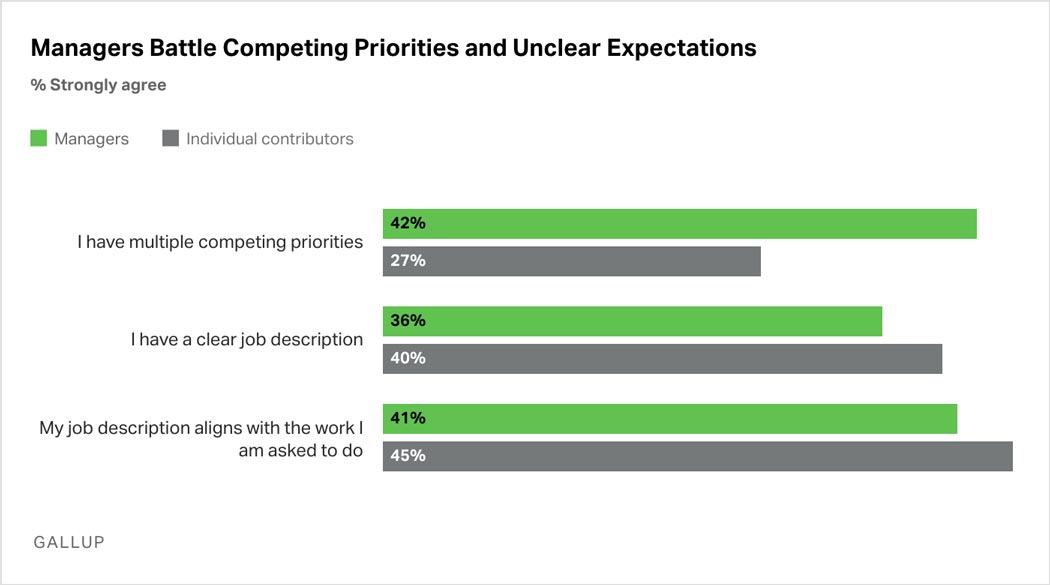

Forty-two percent of managers strongly agree that they have multiple competing priorities, compared with 27% of individual contributors.

Success in any role requires clear, achievable work expectations, yet this basic need often goes unmet for employees.

Globally, only half of employees strongly agree that they know what is expected of them at work. Even more disturbing is that a manager is less likely than an individual contributor to know what's expected of them at work.

The problem begins with managers' formal work expectations. Less than half of managers (41%) strongly agree that their job description aligns with the work they do. The misalignment between formal work expectations and what is actually required of them daily contributes to confusion and sows distrust toward corporate processes and formal communication in general.

Of course, some of the ambiguity is due to managers being in a relatively complex and ambiguous role. Managers have the autonomy to choose how work gets done and how problems get solved. Flexibility in how work gets done is important because solutions to the problems that managers are tasked with solving are not always obvious.

However, managers aren't all-powerful or all-knowing. They may lack context or authority to make confident decisions. Or, they may feel they're given unfair or unrealistic expectations at work when suddenly held responsible for unexpected situations -- for example, having to deal with an angry customer, an employee's personal issue, a scheduling error or a vendor who didn't meet expectations.

Another big cause of confusion for managers is that they tend to wear many hats -- and their commitments to multiple bosses, employees, customers and stakeholders are often in conflict.

This experience does not occur as much for individual contributors. In fact, managers are 56% more likely than individual contributors to strongly agree they have multiple competing priorities.

Competing priorities are especially difficult to handle if managers do not receive enough leadership support when setting and resetting priorities. And when managers have unclear expectations, their confusion affects peers and direct reports.

"My biggest challenge is managing expectations. The expectations of leadership and my team do not always align."

2. Heavy Workload and Distractions at Work

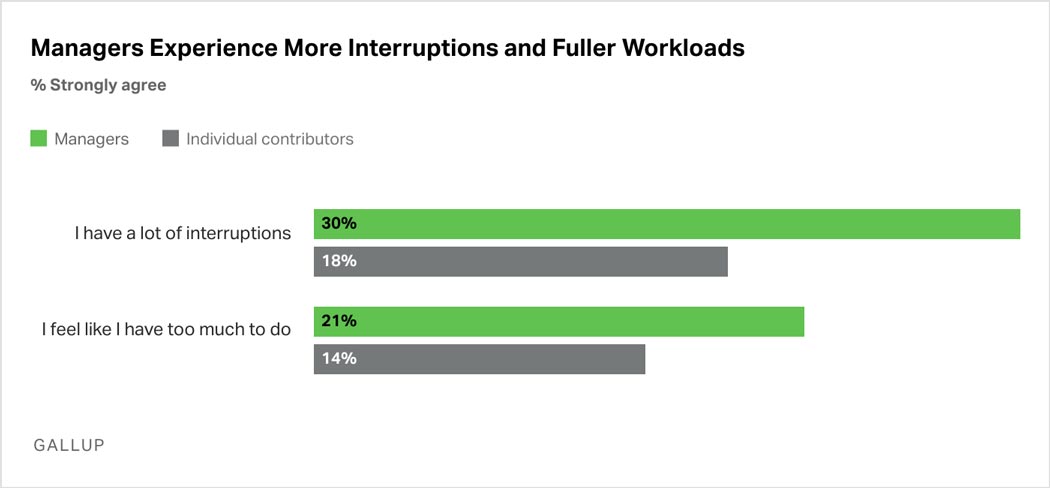

Managers are 67% more likely than individual contributors to strongly agree they have a lot of interruptions at work.

And managers are 50% more likely than individual contributors to strongly agree they "have too much to do."

On average, managers report working about four more hours per week (or an extra half-day) than individual contributors. How that time is spent depends a lot on the responsibilities of the manager.

Part of a manager's heavy workload is due to their role in communicating expectations across many stakeholders. When new work expectations are set, priorities change or progress needs to be discussed, managers are responsible for relaying that information. Consequently, they spend a lot of time in meetings, communicating with team members, peers and leaders.

Managers spend 21% more of their time in meetings than their employees do, and after the meetings are done, managers still must complete their own work, which can create time management challenges.

Also part of a manager's daily duties is dealing with interruptions and distractions at work: Managers are 67% more likely than individual contributors to strongly agree they have a lot of interruptions at work.

When something goes wrong or an important decision needs to be made, managers must often drop what they are doing and get involved. Numerous distractions at work can affect their ability to focus and perform at high levels.

Not to mention, when they spend much of their day in meetings, their team members are left waiting to get direction, approvals and feedback from them.

Managers often feel "stuck in the middle" between managing their direct reports and reporting to their leaders. For example, leaders may require standing meetings to keep managers accountable, which can add days to a project's completion while individual contributors wait for approvals and feedback.

Achieving what is required by their boss and ensuring their team has what it needs to be successful can be challenging and can elevate job stress.

"The manager often gets stuck in the middle -- there's a lot of pressure playing middleman/woman to balance the desires of leaders and employees."

3. Job Stress and Frustrations

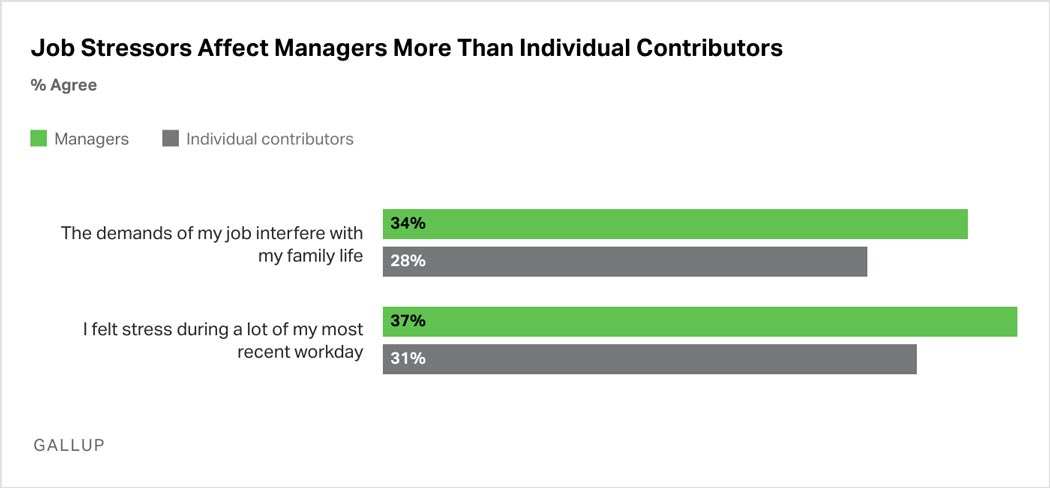

Managers are 27% more likely than individual contributors to strongly agree that they felt stress during a lot of their most recent workday.

Like most stressful jobs, life as a manager can be emotionally and cognitively draining. Managers routinely make high-pressure, high-stakes decisions that have financial implications for their employer and employees.

They step in when a customer experience is in trouble. They deliver the bad news of budget cuts and downsizing. Even on an easy day, they are responsible for the livelihood, wellbeing and future of their employees.

They are in the spotlight all the time, constantly under scrutiny and always having to justify their actions, and the decisions they make may follow them for the rest of their career.

In short, being a manager involves considerable job stress. Managers are 27% more likely than individual contributors to strongly agree that they felt stress during a lot of their most recent workday.

For these reasons, managers are at significant risk of burnout. An unmanageably heavy workload and unreasonable time pressure are two of the top five predictors of burnout -- and they are all too common for managers.

Employee burnout is serious. Gallup's research has found that burnout has a direct effect on health, relationships, performance and career growth.

Getting clarity on work expectations, priorities and key partnerships so that managers can see a manageable path forward is critical. But it's also important to remember that managers are humans with feelings and may need numerous ways to manage stress.

One path to stress management is intentionally building strong interpersonal relationships. Support from a boss and peers can help managers stay positive.

Unfortunately, managers don't have a lot of opportunities to spend time with people who recharge them. Managers are less likely than individual contributors to strongly agree that they liked who they worked with and liked what they did on their most recent workday.

Managers may spend more time than they would like with difficult employees, while spending too little time with star employees who are more enjoyable and rewarding to coach.

Stop burnout in its tracks. Discover the causes and cures of burnout.

- Create manager networks and workshops that help managers support and learn from one another.

- Build a wellbeing program specifically for the needs of managers.

4. Less Focus on Manager Strengths

Managers are 11% less likely to strongly agree that they have the opportunity to do what they do best at work.

A front-line manager may have an accounting issue, a computer crisis and a scheduling snafu, all in the same shift. And they are expected to be an expert at handling all of it.

They may have remarkable interpersonal skills but fall short on engaging their team because they are spending their afternoons studying spreadsheets.

Most managers become managers after being an exceptional individual contributor or by simply sticking around for a long time. But, as many new managers can attest, being a successful manager takes a completely different skill set than what's needed to work effectively in an individual role.

Many talented people who are highly successful employees are not talented as managers. A new manager may have been promoted because of their exceptional customer service skills, but now they are expected to develop, inspire and get work done through others.

Gallup has found that most employees do not have a natural aptitude for management, but they feel trapped because the management track is the only path to career advancement they can see -- the only way to increase pay or develop professionally.

Managers do their best, of course, but without additional support and training, they and their teams may suffer.

The personal consequences are severe when an organization positions successful individual contributors in a manager role without them having the right talents to succeed. When managers do not have the natural abilities and aptitude to be a manager, they tend to experience substantially lower engagement and performance while increasing risks of stress, frustration, turnover and burnout. And these issues are often passed on to the team they manage, causing engagement, performance and retention issues for everyone else.

Also, managers often are asked to do work that is outside their sphere of responsibility or capability. Managers are 46% less likely than individual contributors to strongly agree their work is delegated to them properly.

Many leaders assume managers will take care of various issues without being told expectations or receiving additional resources to support their efforts. Sometimes the expectations are clear but well outside the manager's strengths.

It's difficult to be strong at the vast array of things managers are asked to do. As a result, managers spend significantly less time than individual contributors doing what they do best.

Strengths-Based Management

When managers don't know their areas of natural talent, their performance suffers, even if they're a good fit for the position. When people know what they do best and are able to practice and develop their strengths, numerous benefits materialize.

Give managers a snapshot of their natural pathways to success by utilizing the CliftonStrengths assessment. Once they know their CliftonStrengths, they can begin to focus and develop what they do best.

"Success is different as a manager because it comes from other people's success."

- Make a list of what a manager does best and ask them to list what they think they do best. Talk about how they can spend more time playing to their strengths and building strong partnerships.

- Have your managers take CliftonStrengths and write a plan for how they can use their strengths to achieve their most important performance and development goals.

- Ask a manager's coworkers to list what strengths they would like to see the manager use more often.

5. Frustrating Performance Reviews

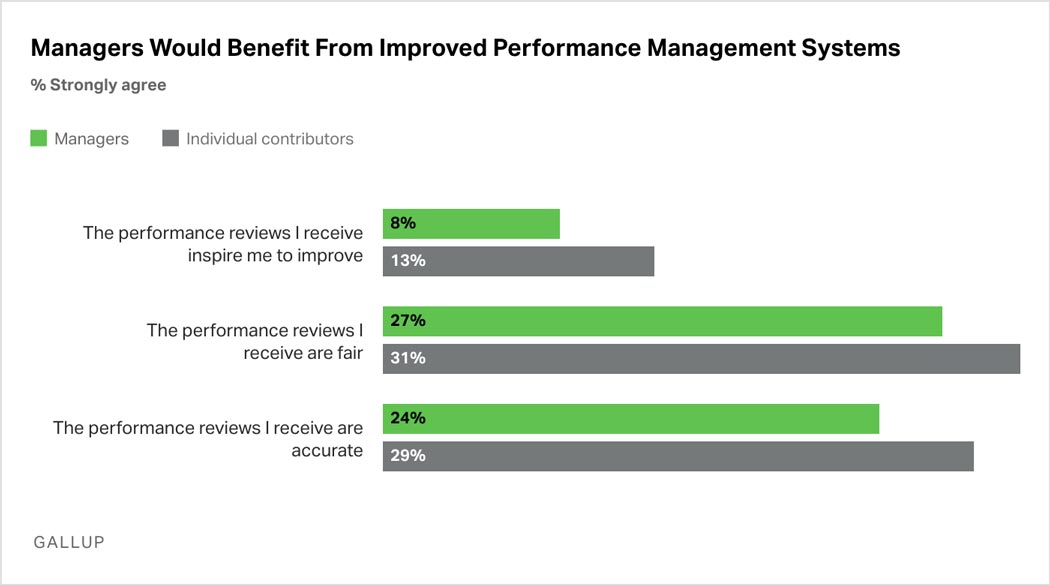

Only 8% of managers strongly agree their performance reviews inspire them to improve.

In recent years, traditional performance management systems have been under fire. After investing significant resources and time, many organizations are realizing that their annual employee performance reviews do not improve performance -- and, in many cases, they actually hurt performance.

Astoundingly, managers report an even worse performance review experience than individual contributors. A mere 13% of individual contributors strongly agree their performance review inspires them to improve, but that percentage is a microscopic 8% for managers. They also find the performance review process to be less fair and less accurate than individual contributors do.

If there were a single argument against the traditional performance review, it would be this: Those administering performance reviews think less of the process than those receiving them.

When managers experience unfair and inaccurate performance reviews, they aren't receiving the critical feedback, coaching and recognition they need to thrive, hindering their effectiveness, development, and long-term career potential. Then managers are asked to repeat that same ineffective, frustrating process for those who report to them.

It's time for organizations to re-engineer their performance management systems. Modern performance management must shift to a performance development approach that equips, inspires and improves performance.

Gallup's analysis finds that performance reviews are not enough. Managers must be trained to have continual, meaningful performance conversations with their team members.

- Have regular check-ins with managers to discuss their performance. Formal manager performance reviews should never be a surprise.

- Don't get lost in poor performance metrics. Rethink how you can use clearly defined goals and behavioral evaluations in place of performance metrics that don't fully capture their responsibilities and contributions.

05 What Are the Perks of a Being a Manager?

There's no shortage of manager perks. Managers are allowed autonomy -- freedom and creativity -- in how they accomplish their career goals, and their opinions are influential. Managers spend their days in collaboration and interacting with a variety of people, which makes work more interesting and positions them for advancement.

Also, they are more likely than individual contributors to see how their incentive pay connects to business success, giving them direction and motivating them to do what's best for the organization.

The top five perks of being a manager:

1. Involvement in Decision-Making

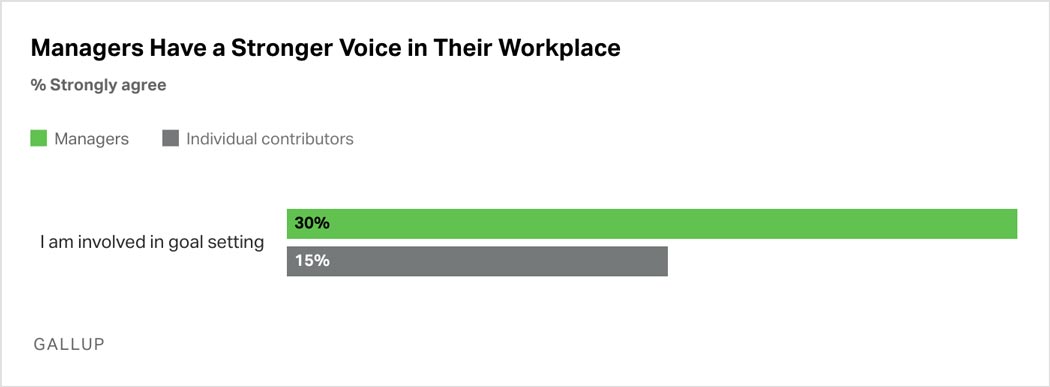

Managers are 31% more likely than individual contributors to strongly agree that their opinions count at work.

Having a voice that matters is a hallmark of being a manager. Managers have decision-making power on their teams; they get to call the shots and choose how to develop individuals into future stars.

Employees look to their manager as their coach and guide, as well as the gatekeeper to their destiny and development opportunities at an organization. Managers play the role of mentor, advice-giver and rescuer when trouble comes.

Beyond their one-on-one relationships with team members, managers are responsible for executing a business strategy. Naturally, managers have more decision-making control than individual contributors over establishing their own goals and strategies.

In fact, managers are twice as likely to strongly agree they are involved in setting goals for themselves and others. Having a voice and involvement in goal setting is an important aspect of creating goals that motivate employees.

It ensures that goals address the most important aspects of the job and inspire strong performance. Involving employees in this decision-making process also encourages them to take ownership of their goals.

Although managers have more ownership of their goals, there is a lot of room for improvement in this area. One of the most important responsibilities of a manager is to know what is achievable for themselves and their team.

Setting the right work expectations, making necessary adjustments and making wise -- albeit, sometimes bold -- decisions greatly influence whether managers and their teams succeed. As a result, leaders (managers of managers) need to give managers the decision-making power and support they need to set priorities that make sense for both them and the organization.

In addition to having a voice regarding their team, managers have access to organizational decision-makers, and their opinions with those influencers are valued more highly than those of individual contributors. Managers are included in more forms of organizational communication, and managers even receive more surveys from their organization than individual contributors do. And, managers are more likely than individual contributors to be asked about their organization's strategy and actions.

Not surprisingly, managers are 31% more likely to strongly agree that their opinions count. From having command over their team to having a voice in organizational decisions, managers are well-positioned to feel highly valued and confident about their status within the organization. They also tend to identify more strongly with the mission and vision of their organization because they have decision-making power and a voice in how things get done.

"Managers should be the voice of their team. They need to share important feedback from their team with the right parties, like leaders, other managers and other teams."

- Ensure managers have a chance to hear from their boss' boss.

- Connect managers' work to the purpose, brand and culture of the organization.

- Hold managers accountable for making their teams aware of key organizational messages and decisions.

2. Autonomy and Control Over Their Work

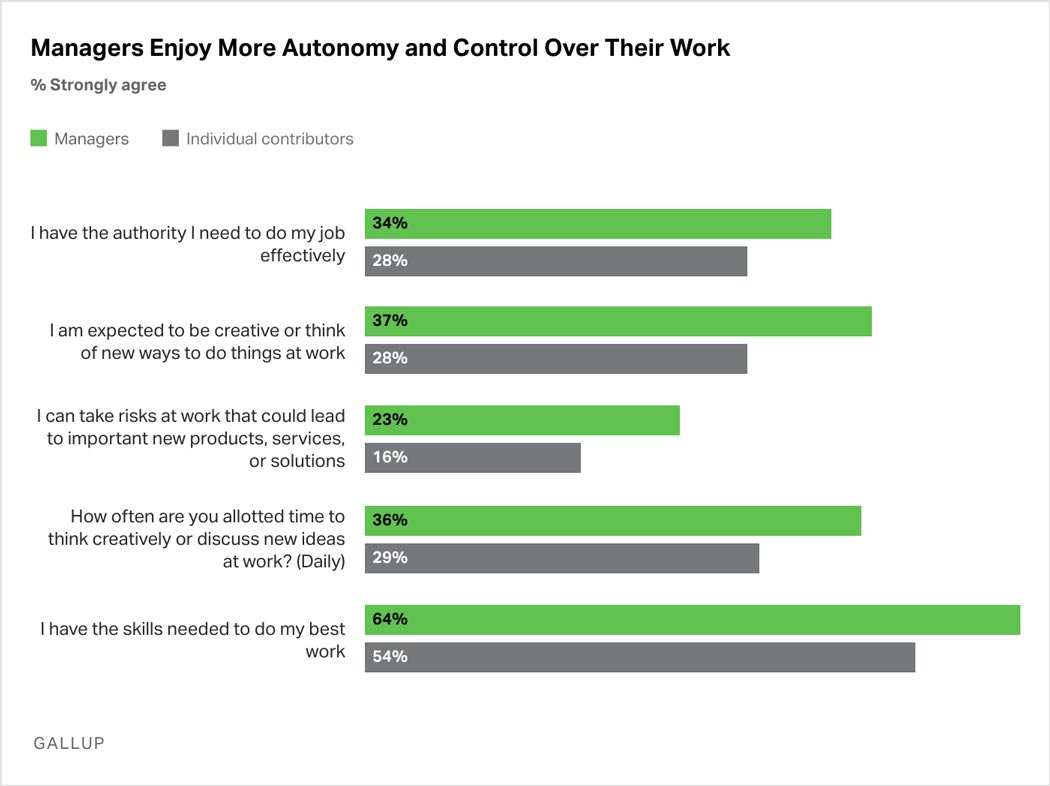

Managers are 24% more likely to have "time to think creatively or discuss new ideas at work" daily.

Managers have a greater say than individual contributors in the organization's strategy and goals. They also have greater autonomy in deciding how their work gets done. Managers are 21% more likely to strongly agree that they have the authority they need to do their job effectively.

Many people take for granted that managers can choose what to work on, how to work on it, when they will work on it and who they can ask to get involved.

Autonomy at work is a top predictor of performance. It empowers employees to approach complex tasks in a way that works best for them, and it creates intrinsic motivation by allowing employees to take ownership of their work. Of course, too much autonomy can be disorienting and confusing -- but, as a rule, the more control someone has over their work, the better they feel about it.

Autonomy has other benefits as well. It encourages creativity in problem-solving. Managers are more likely to have expectations for being creative or thinking of new ways to do things at work. They are also more likely to feel empowered to take risks that could lead to new products, services or solutions. An individual contributor may have ideas about how to, say, make customers happier or eliminate wasteful processes, but it's the manager who has the autonomy to test those ideas.

Ultimately, managers have the decision-making power to shape the direction of their work, to find new paths and to take action that makes those new paths successful. All of these abilities contribute to greater optimism about work, in general.

Managers are 36% more likely than individual contributors to strongly agree that their work is achievable.

"I need autonomy and trust from my organization to make decisions that are best for my team and organization."

- Managers should approach their job in whatever way works best for them, as long as they effectively engage their team and achieve the required outcomes.

- Help managers name and empower their own set of "lieutenants" who will take responsibility for getting work done.

- Continually clarify expectations and priorities for managers so that autonomy doesn't turn into too much ambiguity.

3. Collaborative Work Environment

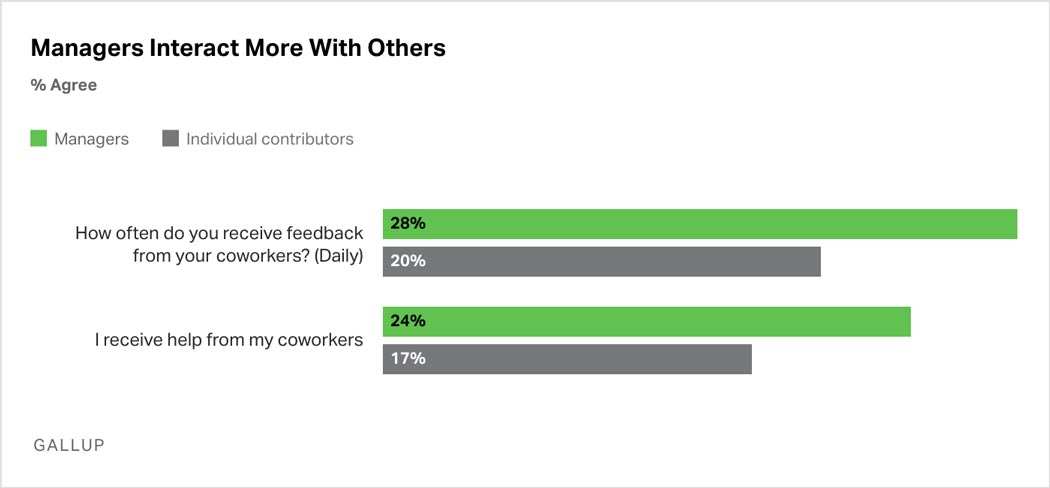

Managers report spending an average of about five hours a day working with other people. That's five more hours a week than individual contributors spend working in collaboration.

Unlike many individual contributors who may spend most of their day working alone, managers are typically at the center of interpersonal activity at work, reaping the benefits of collaboration. Managers spend more than half of their time in collaboration with others, checking in with teammates, leading meetings, interacting with customers and negotiating with vendors.

They are required to have relationships across the organization to be successful, and they often interact with interesting people outside their team or department. One of the biggest perks of being a manager is being well-informed and highly connected.

Managers report spending an average of about five hours a day with other people, which is 26% more time in collaboration than the average individual contributor. Managers' time with coworkers includes everything from leading a brainstorming session to interviewing job candidates to having lunch with another manager.

Many workplaces are built with the intention of helping managers lead collaboration. Managers are about twice as likely to be on a matrixed team, which means they work with multiple teams and have multiple bosses. Matrixed teams are engineered to create an extremely collaborative work environment, which occurs when people are interdependent -- it's their job to do work in collaboration with one another.

This type of dynamic, ever-changing environment can be stimulating and motivating for managers. Something is always happening.

The collaborative nature of their role naturally helps managers be more informed and resourceful. Managers are more likely than individual contributors to receive help and daily feedback from their coworkers.

And managers receive more frequent feedback from their own boss. Managers are essentially at the center of an ecosystem designed to keep them up-to-date and responsible for getting work done through others.

Over the long term, frequent conversations with a variety of people can lead to new learning, advancement opportunities, developmental feedback and a general sense of being "in the know" about what's happening across the organization.

Managers who coach, win. Sign up for our all-in-one coaching course, Gallup Global Strengths Coach. Attend in-person or online.

"The benefit of collaboration is the mutual knowledge that we are in this together."

- Teach managers to ask for feedback from their direct reports and become masters of two-way conversations.

- Discuss when and why work should be done together as a group versus independently.

- Improve cross-functional collaboration and break down silos by requiring managers to regularly work with one another or job shadow another manager for a day.

4. Career Advancement and Development Opportunities

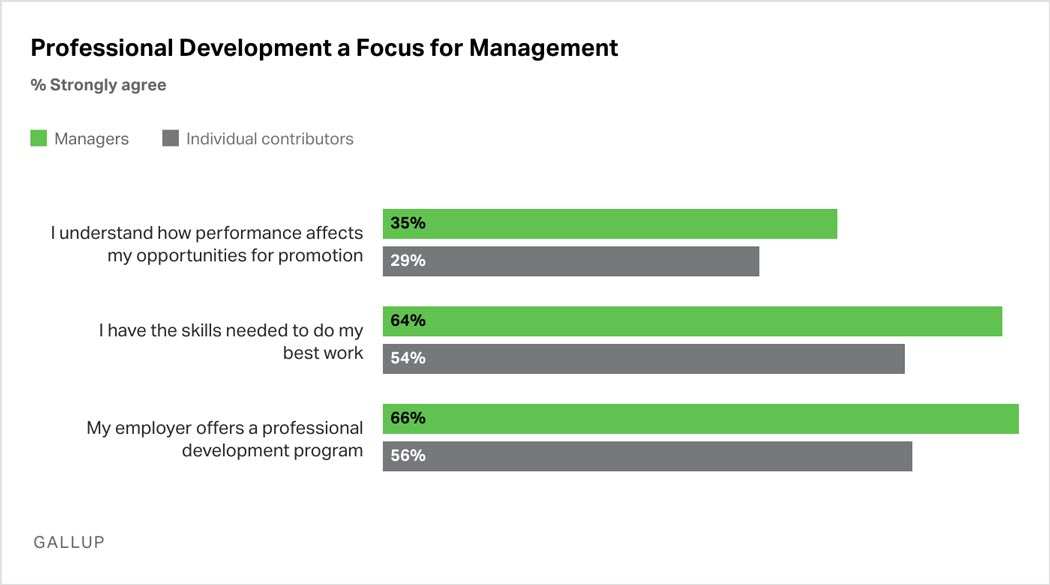

Sixty-six percent of managers report having a professional development program.

Opportunities to learn and grow are the top reason younger generations of employees are attracted to an organization. Millennials, in particular, desire development opportunities at work. Lack of opportunities for development and advancement is the top reason employees of all ages leave an organization. In other words, employee attraction and retention are strongly tied to personal growth, career development and seeing a positive future with an organization.

Often, organizations target these critical employee needs with a formal professional development program, engineered to help employees craft career-development goals, build skills and seek key experiences for a successful future.

Managers have a significant edge when it comes to formal professional development opportunities, as about two-thirds of managers report being in a professional development program. Additionally, managers are 24% more likely than individual contributors to have a mentor who helped them in the last week. Clearly, organizations see the benefit of building manager strengths.

And, a manager's edge in developmental opportunities does seem to make a difference: Managers are 19% more likely than individual contributors to strongly agree they have the skills to do their best work, and they are 17% more likely to strongly agree that their skills and experience are fully utilized in their organization.

Despite this special attention on management development, however, Gallup's data show that organizations have a long way to go when it comes to developing managers' skills and creating a clear career path for quality managers:

- Only slightly more than one-third of managers strongly agree they have had opportunities at work to learn and grow in the last year.

- Thirty-six percent of managers do not fully believe they have the skills they need to do their best work.

- Sixty-five percent of managers do not strongly agree that they understand how their performance affects their opportunities for promotion.

Leaders may think they are doing a lot, while managers feel that it isn't enough. Here are two important questions to ask:

- Are our development programs integrated enough with the realities of our workplace?

- Are managers experientially learning and growing on the job, and are they getting enough key experiences that build strong people leadership?

Many management development programs are positive experiences but don't affect the real experience of work, so it's important to examine your development program's effectiveness.

- Are our managers having frequent conversations with their supervisors about their future with the organization?

- Are our managers learning best practices and tips from their peers?

Experiences and relationships are everything when it comes to personal growth. Managers need to have an ongoing dialogue with their bosses about their future, their dreams and what they can be doing now to achieve higher performance.

"My people have developed me and taught me how to manage. I've learned so much by listening to them and what they need."

- Define key experiences that help managers develop.

- Map out pathways for career advancement with managers.

5. Motivating Pay Incentives

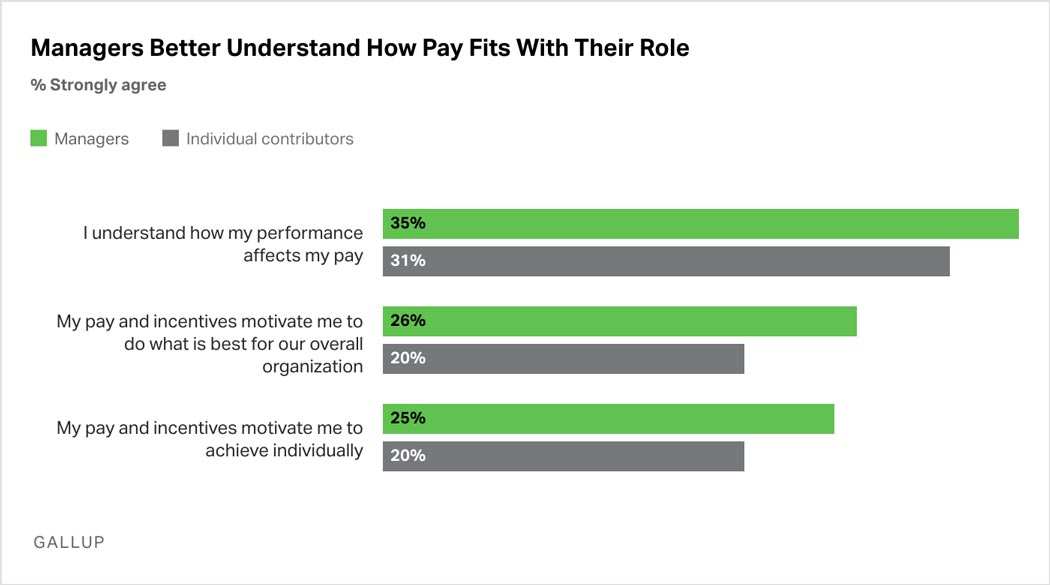

Managers are 25% more likely than individual contributors to strongly agree that their pay and incentives motivate them to achieve individually.

Pay is a significant motivating factor for managers. In general, the average annual wages for U.S. individual contributor employees is significantly less than the salaries of managers, with ranges varying by roles and industries. Not surprisingly, managers are 13% more likely to report high levels of financial wellbeing.

But there's a deeper story when it comes to motivation. Employees complain the most about pay when they feel it is unfair and inaccurate. The solution is to ensure that employees believe their pay is within their control and understand how to influence future compensation.

Regular, transparent conversations about pay are key. Employees need to understand pay structures, philosophies and actions they can take to progress financially in their careers.

Managers seem to understand this context better than individual contributors. Managers are more likely than individual contributors to strongly agree that they know how their performance affects their pay. They also say they have greater autonomy and control over their work, and they are more likely to see a clear promotional path to higher earnings.

When people can see a reward clearly and feel empowered to attain it, they are naturally more motivated. Managers are 25% more likely to strongly agree that their "pay and incentives motivate me to achieve individually."

And there's another factor to consider: Managers are more likely to understand how their performance connects to team and organizational success -- they see how their personal achievement connects to the greater good. Managers are 21% more likely to strongly agree that they see how their own goals connect to the organization's goals. Not surprisingly, they are also more likely to strongly agree that their pay incentives motivate them to do what is best for the organization.

Higher pay makes being a manager an attractive proposition, but a manager's knowledge about the pay system and how to navigate it is perhaps even more inspiring than the money itself.

- Measure manager performance using a balanced scorecard that includes quantitative metrics and subjective evaluations. Don't incentivize any one metric with too much pay.

- Don't forget to make performance pay discussions just as much about recognition of a job well done, as about money.

- Include team collaboration, customer engagement and learning goals as key outcomes that are incentivized.

06 Is Management a Good Career Choice?

The short answer is, "it depends."

Navigating the challenges of being a manager and taking advantage of the role's unique opportunities can be a balancing act.

Often the advantages of being a manager can be a double-edged sword. While some of the biggest perks of being a manager are having a voice in organizational decision-making and having autonomy in how work gets done, these advantages can lead to ambiguity, complexity and competing priorities.

Similarly, it's great that managers have such a collaborative work environment, but managing various types of employees and stakeholders escalates job stress and frustrations.

A manager can sometimes struggle to secure protected time to think, do their own work and respond to requests.

When it comes to their future, managers certainly have opportunities for development and advancement, but these programs sometimes fall short. Managers spend less time doing what they do best than individual contributors do, despite managers having more opportunities for development.

The story is similar to how managers experience performance management. While they can see the connection between their pay and performance, they don't necessarily have an effective performance management system.

The decision to pursue a manager position should not be made lightly, as even the perks of being a manager come with their challenges.

07 How Can Leaders Better Support Their Management?

Leaders often forget that managers are employees too. They experience hiring, onboarding and performance reviews just like everyone else. How they feel about your organization's mission and culture are significantly shaped by these touchpoints.

Leaders can promote a better management experience by taking the following actions:

1. Ensure your managers experience and promote your purpose, brand and culture at every stage of the employee life cycle.

The CEO, CHRO and executive committee need to clearly identify and communicate to managers the organization's purpose and how they want applicants, employees and customers to perceive their brand.

They also need to portray the organization's desired culture. Leaders have more clarity on their aspirational culture than managers do. But an organization's real culture is the one that managers express.

The way they demonstrate the organization's culture influences how everyone on their team reacts to culture change and experiences the stages of the employee life cycle, from hiring through departure -- and those employee experiences affect the management experience.

Also, when managers grasp their organization's purpose, brand, and culture, they will better understand how their performance affects the company's success, how their goals tie to the organization's goals, and how their pay and incentives tie to their role in the organization's success.

And they will be more effective at leading their teams. How can employees have a positive employee experience at each stage of the employee life cycle without their manager being clear on how to embed the culture in each stage?

2. Redefine the role of manager from boss to coach.

The work expectations for managers are often messy, contradictory or incoherent. Organizations need to redesign the business manager role, so it is clearly defined as a people leader role and so that managers are given the time, training and support they need to coach their teams effectively. In other words, a manager's role should be one of people management.

This role should also be responsive to a changing workplace that is more matrixed, flexible and autonomous than generations before.

Gallup's research shows that today's employees want a coach, not a boss. The transition from boss to coach means managers are expected to do more than delegate. Their job is to develop stars in an individualized manner through collaborative goal setting, future-oriented coaching and achievement-oriented accountability.

Coaches lead great conversations with their employees -- they don't just talk at them and give feedback.

3. Select your managers based on their aptitude for management.

Organizations set managers up for success by making sure they've selected the right person for the role. That means selecting someone with innate leadership traits.

This is best done through scientific assessments that measure innate tendencies, behavior interviews, and a systematic review of key experiences and proficiencies. Instead of making management a default reward for high performance in individual contributor roles, leaders should realize that not everybody is cut out for the job.

This may require creating a nonmanager, individual contributor development track that keeps high performers growing without shifting them into management.

4. Design manager learning programs that are continual, multimode and experiential.

Managers receive more training than individual contributors. However, their training doesn't always translate to more confidence on the job.

The best development plan for managers is not a compilation of one-time "events," but, rather, it teaches fundamentals of coaching that endure.

Organizations need to deliver learning and development opportunities and experiences that are multimode, relevant and strengths-based. Great management development programs create a learning journey that blends powerful in-person experiences with on-the-job experiential learning and just-in-time resources for common challenges and conversations.

Consider trainings that include simulations or role-play -- for example, having a casual check-in with a direct report -- or find creative ways to integrate training exercises into live work experiences.

5. Require leaders to give meaningful strengths-based feedback to managers once a week.

Leaders need to have coaching conversations with the managers who report to them. Everyone needs a coach, and for managers to transition from being a boss to being a coach, they need good feedback, development and recognition from their leader.

By delivering meaningful feedback, leaders can bring manager learning programs to life, model great coaching and identify further development needs.

Gallup also finds that both coaching and management development programs that build on the strengths of individual managers outperform the approaches that are not strengths-based. That is, managers develop best within the context of who they naturally are and what they do best.

Leaders do not develop great managers by teaching them transactional knowledge, providing a checklist of things to do or prescribing them a basic set of questions to ask their employees.

Learning experiences should encourage management to find creative solutions to problems using their unique set of strengths. Leaders can bring these learning experiences to life by providing continual feedback and coaching that is individualized to the manager's strengths and weaknesses.

6. Design a succession planning system that considers criteria that predict effective people management.

In many organizations, succession planning is primarily a subjective process. It's prone to bias that results in poor decision-making, which places people into roles where they lack the capacity to perform. Even worse, many organizations have no succession plan at all.

There are ways, however, to stack the odds in your favor when it comes to promoting the right people. Gallup recommends starting with objective performance measures and scientifically validated assessments of natural manager talent to determine who has the potential to be promoted to a people leader role. Then, combine that data with key experience inventories that correlate with leadership success.

Key experiences might include gaining international experience, learning deeply about customers, building cross-segment relationships or leading a team through adversity.

Practice makes everyone better and gives you a glimpse into how employees are likely to perform in the role they are auditioning for.

08 How Gallup Can Help

Gallup knows more about managers than anyone else in the world -- and we have proven experience in turning that knowledge into behavioral changes that improve business outcomes. Gallup helps the world's leading organizations:

- attract and hire high-talent managers

- develop managers who drive results

- support managers with our digital platform, Gallup Access