In the intense competition to attract and retain top talent, U.S. employers are vying to offer the most alluring perks imaginable to their workers. Companies such as Google are leading the trend, hoping that happy employees are more productive, creative, and passionate workers.

A massage at work would probably make anybody happier. But happy doesn't necessarily equal productive, or even loyal.

On the surface, it's hard to argue with this approach: A free lunch, a siesta in the nap room, or a massage at work would probably make anybody happier. But happy doesn't necessarily equal productive, or even loyal.

Gallup recently studied the relationship between workplace policies and employees' engagement and well-being and found that indulging employees is no substitute for engaging them.

Engagement eclipses workplace incentives

Gallup research shows that keeping employees happy or satisfied is a worthy goal that can help build a more positive workplace. But simply measuring workers' satisfaction or happiness levels is insufficient to create sustainable change, retain top performers, and improve the bottom line. Satisfied or happy employees are not necessarily engaged. And engaged employees are the ones who work hardest, stay longest, and perform best.

"If you're engaged, you know what's expected of you at work, you feel connected to people you work with, and you want to be there," says Jim Harter, Ph.D., Gallup's chief scientist of workplace management and well-being. "You feel a part of something significant, so you're more likely to want to be part of a solution, to be part of a bigger tribe. All that has positive performance consequences for teams and organizations."

By shifting the focus to employee engagement, companies are more likely to motivate their workers to expend discretionary effort and reach their performance objectives. Gallup research has linked employee engagement to nine specific business outcomes -- such as higher productivity, profitability, and customer ratings -- that directly affect the bottom line. And none of them have anything to do with a "bring your dog to work" policy.

According to Gallup research, workplace engagement levels eclipse the effect of policies such as hours expectations, flextime, and vacation time when it comes to employees' well-being. For instance, engaged employees who took less than one week off from work in a year had 25% higher overall well-being than actively disengaged associates -- even those who took six weeks or more of vacation time.

Of the workplace benefits Gallup studied, flextime yielded the strongest relationship to overall well-being among employees. Engaged employees with a lot of flextime had 44% higher well-being than actively disengaged employees with very little to no flextime. Among employees who were not engaged or who were actively disengaged, those who reported having flextime also had higher overall well-being compared with those with very little or no flextime.

The upshot is that an engaging workplace increases the odds of higher employee well-being, regardless of policy or incentives. Employee engagement matters most -- fewer hours with more vacation days and flextime cannot fully offset the negative effects of a disengaging workplace on well-being. Gallup has found that higher engagement levels can insulate employees from everything from a significant downturn in mood on Monday mornings to high stress levels typically resulting from long commutes. And well-being can prevent a lot of sick days.

"Both engagement and well-being relate to health, and healthier people are more likely to go to work," says Harter. "If people are engaged at work and thriving in their overall well-being, they're more agile and resilient and are less likely to be sick, but they're also more likely to want to be in the office."

Some advantages to working remotely

Another popular trend -- working remotely -- has garnered headlines, with Yahoo CEO Marissa Mayer requiring the company's remote workers to return to the office. Mayer made the point that employees working from home have fewer chances to collaborate with colleagues. While this may be true, Gallup found that companies that offer the opportunity to work remotely might have some advantages when it comes to employee engagement.

But not every employer has embraced this trend, and in some workplaces, working remotely may not be feasible. To learn more, Gallup used these two questions to determine which employees could be classified as remote workers:

- In a typical week, approximately how many hours do you spend at your primary job?

- Is any of this time spent remotely or in a location different from your coworkers?

Based on these criteria, Gallup found that nearly four in 10 (39%) of the employees surveyed spend some time working remotely or in locations different from their coworkers. Though they do not have a manager nearby to monitor their productivity, remote workers log an average of four more hours per week at their primary job than their on-site counterparts.

Despite working longer hours, working remotely seems to have a somewhat positive effect on workers' engagement levels. Gallup found that slightly more of these employees are engaged (32%) than employees who work on-site (28%). (See sidebar "Remote Workers Log More Hours Per Week.")

Balancing collaboration and camaraderie with a sense of freedom

There is a point of diminishing returns for engaging remote workers. Those who spend less than 20% of their time working remotely are the most engaged, at 35%, and they have the lowest level of active disengagement, at 12%. These employees likely enjoy an ideal balance of both worlds -- the opportunities for collaboration and camaraderie with coworkers at the office and the relative sense of freedom that comes from having the option to work remotely. By contrast, those who spend more than half of their time or all of their time working remotely have similar engagement levels as those who do not work remotely.

On-site employees score higher than remote workers on the item "I have a best friend at work" on Gallup's 12-item employee engagement survey, the Q12. This suggests that remote workers may miss important social and collaborative opportunities that are integral to engagement and well-being. On the other hand, remote workers score higher on the Q12 items "At work, my opinions seem to count" and "The mission/purpose of my company makes me feel my job is important," which are typically associated with a sense of belonging.

This seems to indicate that remote workers may feel more connected to their companies, despite the physical distance between themselves and their workplace and colleagues. This intrinsic sense of connection to their companies may help explain why these employees have slightly higher engagement and work more hours, even without the direct supervision and positive social interactions inherent in a more traditional workplace setting. (See sidebar "Remote Workers: Balancing Collaboration With a Sense of Freedom.")

What moves your company forward

If you asked your team who would like to take a foosball break or have a chef prepare them a free lunch, you'd be trampled in the rush for the break room. But if you asked if your team felt engaged, you might only see three out of 10 hands raised, assuming your office matches the average engagement of American workplaces.

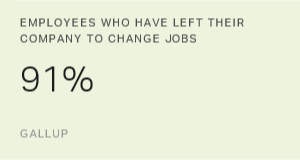

"Leaders will buy miserable employees latte machines for their offices, give them free lunch and sodas, or even worse -- just let them all work at home, hailing an 'enlightened' policy of telecommuting. Hell, some of these practices might even earn your company a business magazine's Great Place to Work award," says Gallup Chairman and CEO Jim Clifton. "The problem is, employee engagement in America isn't budging. Of the country's roughly 100 million full-time employees, an alarming 70 million (70%) are either not engaged at work or are actively disengaged."

Employees may appreciate the perks and presents -- but freebies don't make workers feel engaged. They don't even make workers genuinely happy. Gallup has found that engagement has a greater effect on workers' well-being than any of the benefits it studied.

What workers truly want is an intrinsic connection to their work and their company. That's what drives performance, inspires discretionary effort, and improves well-being. That's what keeps people coming to work, makes them excited about what they do, and inspires them to push themselves and their companies forward. There aren't enough foosball tables in the world to provoke that kind of commitment, and a lifetime supply of latte can't change a disengaged worker's mind.