Management talent exists in every company. It's often hiding in plain sight.

Gallup has found that one of the most important decisions companies make is simply whom they name manager. Yet our analytics suggest they usually get it wrong. In fact, Gallup finds that companies fail to choose the candidate with the right talent for the job 82% of the time.

Bad managers cost businesses billions of dollars each year, and having too many of them can bring down a company. The only defense against this problem is a good offense, because when companies get these decisions wrong, nothing fixes it. Businesses that get it right, however, and hire managers based on talent will thrive and gain a significant competitive advantage.

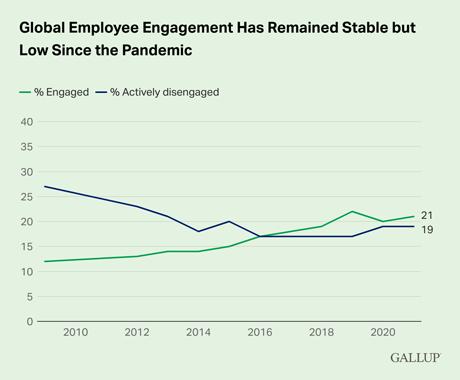

Managers account for at least 70% of variance in employee engagement scores across business units, Gallup estimates. This variation is in turn responsible for severely low worldwide employee engagement. Gallup reported in two large-scale studies in 2012 that only 30% of U.S. employees are engaged at work, and a staggeringly low 13% worldwide are engaged. Worse, over the past 12 years, these low numbers have barely budged, meaning that the vast majority of employees worldwide are failing to develop and contribute at work.

Gallup has studied performance at hundreds of organizations and measured the engagement of 27 million employees and more than 2.5 million work units over the past two decades. No matter the industry, size, or location, we find executives struggling to unlock the mystery of why performance varies from one workgroup to the next. Performance metrics fluctuate widely and unnecessarily in most companies, in no small part from the lack of consistency in how people are managed. This "noise" frustrates leaders because unpredictability causes great inefficiencies in execution.

Executives can cut through this noise by measuring what matters most. Gallup has discovered links between employee engagement at the business unit level and vital performance indicators, including customer metrics; higher profitability, productivity, and quality (fewer defects); lower turnover; less absenteeism and shrinkage (i.e., theft); and fewer safety incidents. When a company raises employee engagement levels consistently across every business unit, everything gets better.

To make this happen, companies should systematically demand that every team in their workforce have a great manager. After all, the root of performance variability lies within human nature itself. Teams are composed of individuals with diverging needs related to morale, motivation, and clarity -- all of which lead to varying degrees of performance. Nothing less than great managers can maximize them.

But first, companies have to find those great managers.

Few managers have the talent to achieve excellence

If great managers seem scarce, it's because the talent required to be one is rare. Gallup's research reveals that about one in 10 people possess the talent to manage. Though many people are endowed with some of the necessary traits, few have the unique combination of talent needed to help a team achieve excellence in a way that significantly improves a company's performance. These 10%, when put in manager roles, naturally engage team members and customers, retain top performers, and sustain a culture of high productivity.

It's important to note that another two in 10 people exhibit some characteristics of basic managerial talent and can function at a high level if their company invests in coaching and developmental plans for them. In studying managerial talent in supervisory roles compared with the general population, we find that organizations have learned how to slightly improve the odds of finding talented managers. Nearly one in five (18%) of those currently in management roles demonstrate a high level of talent for managing others, while another two in 10 show a basic talent for it. Combined, they contribute about 48% higher profit to their companies than average managers do.

Still, companies miss the mark on high managerial talent in 82% of their hiring decisions, which is an alarming problem for employee engagement and the development of high-performing cultures in the U.S. and worldwide. Sure, every manager can learn to engage a team somewhat. But without the raw natural talent to individualize, focus on each person's needs and strengths, boldly review his or her team members, rally people around a cause, and execute efficient processes, the day-to-day experience will burn out both the manager and his or her team. As noted earlier, this basic inefficiency in identifying talent costs companies billions of dollars annually.

Conventional selection processes are a big contributor to inefficiency in management practices; they apply little science or research to find the right person for the managerial role. When Gallup asked U.S. managers why they believed they were hired for their current role, they commonly cited their success in a previous non-managerial role or their tenure in their company or field.

These reasons don't take into account whether the candidate has the right talent to thrive in the role. Being a successful programmer, salesperson, or engineer, for example, is no guarantee that someone will be adept at managing others.

Most companies promote workers into managerial positions because they seemingly deserve it, rather than have the talent for it. This practice doesn't work. Experience and skills are important, but people's talents -- the naturally recurring patterns in the ways they think, feel, and behave -- predict where they'll perform at their best. Talents are innate and are the building blocks of great performance. Knowledge, experience, and skills develop our talents, but unless we possess the right innate talents for our job, no amount of training or experience will matter.

Gallup finds that great managers have the following talents:

- They motivate every single employee to take action and engage employees with a compelling mission and vision.

- They have the assertiveness to drive outcomes and the ability to overcome adversity and resistance.

- They create a culture of clear accountability.

- They build relationships that create trust, open dialogue, and full transparency.

- They make decisions based on productivity, not politics.

Very few people can pull off all five of these requirements of good management. Most managers end up with team members who, at best, are indifferent toward their work -- or, at worst, are hell-bent on spreading their negativity to colleagues and customers. However, when companies can increase their number of talented managers and double the rate of engaged employees, they achieve, on average, 147% higher earnings per share than their competition.

Management talent could be hiding in plain sight

It's important to note -- especially in the current economic climate -- that finding great managers doesn't depend on market conditions or the current labor force. Large companies have approximately one manager for every 10 employees, and Gallup finds that one in 10 people possess the inherent talent to manage. When you do the math, it's likely that someone on each team has the talent to lead -- but chances are, it's not the manager. More than likely, it's an employee with high managerial potential waiting to be discovered.

The good news is that sufficient management talent exists in every company. It's often hiding in plain sight. Leaders should maximize this potential by choosing the right person for the next management role using predictive analytics to guide their identification of talent.

For too long, companies have wasted time, energy, and resources hiring the wrong managers and then attempting to train them to be who they're not. Nothing fixes the wrong pick.

A version of this article originally appeared on the HBR Blog Network.

Methodology

Gallup has a five-decade-long history of studying individuals' talents across a broad spectrum of jobs, including numerous studies of managerial talents across a wide range of managerial positions. Talent-based assessments, consisting primarily of in-depth structured interviews and Web-based assessments, have been designed to predict performance, and large-scale meta-analyses have been conducted examining the predictive validity of the instruments. Thresholds in instrument scores are set in an effort to optimize the probability of selecting high performers. Such thresholds, examined across 341,186 applicants and 70 applicant samples from organizations using managerial assessments, were used to inform the percentage of individuals with high and basic managerial talent. These findings were then cross-validated in a random sample of Gallup panelists (n=5,157).

In estimating the percentage of variance in employee engagement that managers account for, multiple regression analysis was conducted across 11,781 work teams examining the relationship between various manager-related independent variables (team members' perceptions of their manager, the managers' engagement, and manager talent) and the team's overall engagement as defined by Gallup's Q12 instrument.

The financial value of manager talent was estimated using standard utility analysis methods that include the relationship between manager talent and financial performance, variability in financial performance across business units Gallup has studied, and the increase in manager talent from the average when an organization selects the top 10% of managers on a Gallup manager talent assessment.