Story Highlights

- Traditional methods of high school rankings are shifting

- Create positive experiences in school by exploring your students' talents

- Better engage your students through CliftonStrengths

American educators, parents and students have debated the value of the traditional high school GPA-based ranking system for some time. Many believe that GPA-based ranking has benefits for students, saying that it celebrates high achievers, positions them as role models, encourages broader courses of study, identifies top picks for college recruiters, and reduces the importance of ACT and SAT scores. Most of all, say advocates, it motivates students to perform.

Others worry that ranking students distracts from the true purpose of school: It can make test scores seem more important to students than actual learning. It may render students reluctant to take tough but truly educational classes for fear of dinging their GPAs. And excellent students may have scores so similar that identifying the top-ranking student requires parsing GPAs into fractions so small that meaningful distinctions are impossible to make.

For those reasons, many high schools have stopped naming a valedictorian and salutatorian altogether. Some now rank students via the broader Latin honors -- magna cum laude, summa cum laude and cum laude.

But that's still a ranking system. And it leaves the big question unanswered -- does rank ordering by GPA improve performance?

Gallup research suggests that it might -- and it might not. Academic motivation is complex and individual. Identifying each learner's unique, intrinsic strengths and building on them more effectively encourages academic success and, perhaps more importantly, engagement.

Develop Engaged and Thriving Students Using CliftonStrengths for Students

Gallup's pioneering, 45+-year research into strengths psychology shows that a person's unique wiring is the basis of his or her innate patterns of thought, feeling and behavior, which the CliftonStrengths assessment categorizes into 34 broad but distinct themes of talent. Those patterns offer clues to an individual's motivation -- what motivates one person can leave another cold.

The human brain isn't fully developed until around age 25, and experience and environment affect theme expression and inter-theme dynamics -- this true for all of us, regardless of age. However, by high school, people are sufficiently old enough that their patterns of thought, feeling and behavior are relatively fixed, and their inborn motivators are active and effective. And the fact is, some people are not motivated by rank systems -- quite the opposite.

Consider the theme of Includer, for instance, which describes a great aversion to making people feel left out, an inevitable result of rank ordering. Or Empathy, a deep awareness of the emotions of others -- GPA-based designations may be less likely to motivate students who lead with Empathy than to provoke commiseration with the students who didn't make the cut.

There are themes, however, that may respond positively to class ranks. People who lead with Competition are liable to make any environment a contest; ranking systems may well inspire them to achieve. Those with a great deal of Significance need to feel known and appreciated for the unique strengths and may be driven to perform if it results in public recognition.

If teachers and parents are serious about students earning better grades and thus higher GPAs, they would do well to identify the individual student's unique strengths rather than rely solely on a ranking system to drive performance. Rankings are neither good nor bad, but the impact of rankings on individual learners can feel positive or negative, depending on the person. That's why an understanding of a student's intrinsic drivers can be a far more effective motivational technique than a ranking system.

But understanding students as individuals may also be a better educational technique too, as Gallup research on student engagement suggests.

Boost Student Outcomes Through Engagement

The Gallup Student Poll, an annual survey of students in grades five through 12 representing thousands of public and private schools in the U.S. and Canada, found in 2017 that only 47% of all students are engaged in their schools.

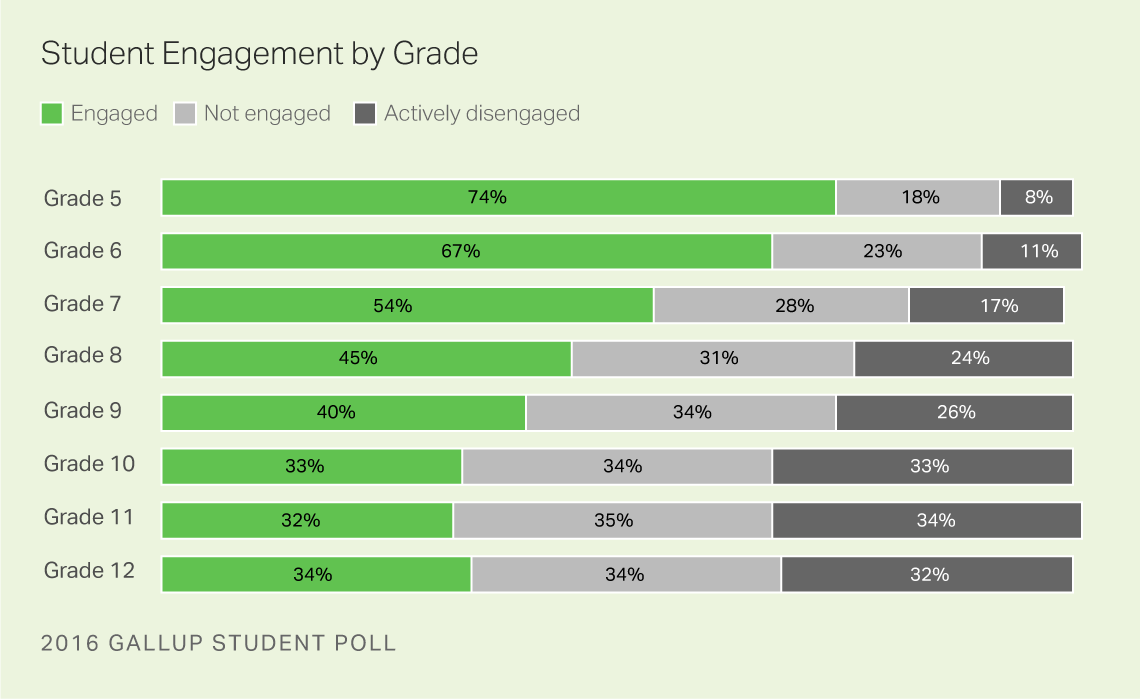

Engagement is defined as having involvement in and enthusiasm for school. Engaged students are emotionally connected to their schools, excited about school and what they're learning, and they contribute to the learning environment. And the research from the 2016 Gallup Student Poll shows that engagement dwindles as students get closer to graduation.

College admissions officials don't evaluate a student's engagement, of course. But parents and high school administrators really should. Actively disengaged students are nine times more likely to say they get poor grades at school, twice as likely to say they missed a lot of school last year, and 7.2 times more likely to feel discouraged about the future than are engaged students. Disengaged students are the least likely to say they get to do what I do best every day, feel safe, have a best friend at school or that their teachers make them feel their schoolwork is important.

Engaged students, however, are 4.5 times more likely to be hopeful for the future, 2.5 times more likely to say they get excellent grades and 2.5 times more likely to strongly agree they do well in school than do disengaged students.

A working knowledge of strengths helps. The opportunity to discover and develop your talents is a positive psychological experience for students, naturally. But it also shifts a student's (and, ideally, a school's) focus from weakness fixing to talent strengthening. Gallup research shows that there is vastly more potential for excellence in a strength than in a non-strength, and that students are more likely to be engaged if they're doing what they do best.

Of course, talent is a broad term, and "what you do best" may not correspond neatly to school subjects. Still, when students learn their innate talents, they have a more positive experience in school -- they become engaged -- and that has a positive effect on grades. A Gallup study of 128 schools in Texas showed that student engagement is significantly related to higher percentages of academic growth across subject areas, along with higher postsecondary readiness in math and writing.

So, while ranking systems have value -- recognizing students for hard work, creating a transparent scale for college recruiters and offering younger students role models -- the limitations are significant, too. Meanwhile, what parents and officials think about ranking systems may not be what students feel about them, not all students, anyway.

Of course, that defeats the goal of either keeping or abolishing a ranking system. That goal should be to create opportunities for each student to be motivated in a way that fits them best so that all students can achieve their best. And a student's best is always driven by the individual's innate strengths.

If administrators and parents intend to develop all students and motivate them to perform, they'll find better solutions within Gallup's research -- and the best solution of all within the students themselves.

Education leaders: Take a closer look at how you can transform your schools:

- Register for the upcoming live webinar Gallup Student Poll Success Story: California's Riverside Unified School District.

- Download our report State of America's Schools: The Path to Winning Again in Education.

- Stay up to date by visiting Gallup's Education Insights, your source for the latest content and advice from Gallup Education Experts.